Meta Rules

Above the rules for any game are the Meta Rules, which apply to all of the games at once. This page covers a variety of higher-level subjects related to pyramid games: Going First, Visibility Issues, Younger Players, Simultaneous Gaming, Pyramid Throwdowns, Scoring with Pyramids, Game Zero, and Playing It Cool.

Going First

Some pyramid games have specific rules for determining who goes first, but many do not. When there is such a rule, it’s usually because there’s some game mechanism already in use that also provides an easy way of choosing a first player, such as by rolling dice.

Some pyramid games have specific rules for determining who goes first, but many do not. When there is such a rule, it’s usually because there’s some game mechanism already in use that also provides an easy way of choosing a first player, such as by rolling dice.

In a few cases, the going-first rule is sort of a joke, such as LaunchPad 23’s rule about being a Rocket Scientist, or Twin Win’s rule about being a Twin (or a Gemini, or Born on the 2nd). In Volcano, where it’s actually kind of a disadvantage to go first, the player who goes first is whoever’s been closest to molten lava. This rule was created so that whoever has to go first gets to brag about that one time when they got really close to molten lava.

The rules for Petri Dish include a fun all-purpose way of determining who goes first in any pyramid game. This is done by cupping a small for each player in your hands, shaking them up, and carefully letting one drop. Or you can have someone else close their eyes and take one out of your hand.

Visibility Issues

One of the advantages of the Pyramid Arcade set is that it contains all ten colors, making it easy to provide accommodations for colorblind players and for anyone playing in low-light conditions.

Before starting any game, make sure all players can tell the difference between each color used, assuming that color matters. (Note that color is irrelevant in some pyramid games, including Treehouse, Martian Chess, Give or Take, Hijinks, and Verticality.)

In most cases, when color does matter, you can choose combinations that allow everyone to see what’s what. Even Color Wheel can be adjusted if needed. Simply substitute the black and white pyramids for the two colors you find most difficult to tell apart.

Note also that the color die uses symbols as well as colors to help with visiblity issues. Remember, the symbols can be understood to refer to whichever five colors you’re actually using in the game.

Younger Players

Kids love the pyramids, but adult supervision is always a good idea with young players, if for no other reason than to make sure none get left on the floor for you to step on later. And of course, the Smalls could be a choking hazard for very young children. But the real issue is that most of the games for the pyramids are too complex for first-level gamers. On the other hand, there are several easy games that are good to start with, and as kids grow they can work their way up to the more difficult games.

Kids love the pyramids, but adult supervision is always a good idea with young players, if for no other reason than to make sure none get left on the floor for you to step on later. And of course, the Smalls could be a choking hazard for very young children. But the real issue is that most of the games for the pyramids are too complex for first-level gamers. On the other hand, there are several easy games that are good to start with, and as kids grow they can work their way up to the more difficult games.

Here are the games in Pyramid Arcade which we think are best suited to try teaching your children first: Give or Take, Nomids, IceDice, Pharaoh, and Pyramid-Sham-Bo. After those you might try Treehouse, Hijinks, Martian Chess, and Verticality.

Some games can also be modified to accommodate younger players. A good example is the Keep-Going Variation of IceDice, which simplifies a core element of the game. (Shelly Roache, former office manager at Looney Labs, created this rule so her kids could play with the grown-ups.)

Similarly, you can make Verticality more playable for youngsters by removing the requirement that each pyramid be touching another. This is known as Skyscraper Style.

Color Wheel is perfect for little helpers. They can help with setup, they can help you look for good moves, and they can help you monitor the Scoring Track.

Lastly, don’t overlook what we call Game Zero: using the pyramids for the simple act of aimless play. Before ever bothering with the rules to an actual game, have fun just messing around with the pyramids. Stack ‘em up and see how tall they’ll go before teetering over. Collect ‘em into groups of size and/or color and stack ‘em up accordingly. Grab a bunch of Larges and stick one on the end of each of your fingertips. Now you have claws. Rraaarrrwww! Just have fun with them!

The Pyramid Throwdown

A Pyramid Throwdown is a multi-stage tournament of pyramid games. A Throwdown should have one game more than the number of players. The first to win two games wins the Throwdown!

First, the games must be chosen. (This process is best conducted with the Reference Cards that come in Pyramid Arcade, but if you don’t have those, you’ll have to make do.) Each player in the Throwdown chooses their favorite game, and places it onto the table for consideration. Each player gets one Veto, and if any are used, the player whose game was vetoed chooses another, until there are as many games as players on the table. This leaves one game still to be selected.

To choose the final game, each player makes a second choice. Any vetoes are handled again, and when there are as many second choice cards selected as there are players, the second choice cards are shuffled together and one is chosen at random, and added to the others selected.

After determining which games the Throwdown will consist of, the cards are then shuffled together and used to randomly determine the order in which the set of games will be played.

Throwdowns will often end prematurely. As soon as one player wins two games, the final games will be rendered moot and won’t need to be played.

The two-player Throwdown is best, since it’s the simplest. As more players are included, it becomes trickier to be sure all the games interact well. Make sure all games chosen are intended for the number of players in the Throwdown. Be aware that with more players, the system becomes more complex and easier to abuse, particularly if combined with Simultaneous Gaming.

Simultaneous Gaming

Many pyramid games, including almost all of the games in Pyramid Arcade, have been designed for concurrent play. This is a signature of Andy Looney’s game design style: He enjoys playing more than one game at the same time, and designs his games accordingly. Wherever possible, players can mentally “check-out” of each game when it’s not their turn, thereby being able to resume focus on another game in which their turn has now come back around. This allows for an overall gaming experience in which all players are constantly engaged, filling the downtime between turns in other games with the time it takes to make a move in each.

Many pyramid games, including almost all of the games in Pyramid Arcade, have been designed for concurrent play. This is a signature of Andy Looney’s game design style: He enjoys playing more than one game at the same time, and designs his games accordingly. Wherever possible, players can mentally “check-out” of each game when it’s not their turn, thereby being able to resume focus on another game in which their turn has now come back around. This allows for an overall gaming experience in which all players are constantly engaged, filling the downtime between turns in other games with the time it takes to make a move in each.

To play more than one game at once, set each game up in its own area of a large table, or gather multiple small tables together, so that each game has its own clearly defined area. Also, establish a Turn Token for each gamespace. (Note that some games have built in Turn Tokens, such as the stack of Dice in Petri Dish, placement of the bag of pyramids in Powerhouse, etc).

When choosing the set of games for simultaneous play, be careful to avoid overlapping parts, and make sure different colors are used as needed to prevent pyramids from one game being mixed into another.

Arrange the seating so that each player can see & reach each game as easily as possible. Ideally you’ll be able to simply rotate in your chair as you complete your turn in one game and turn your attention to your situation in the next.

While this may sound daunting, it actually becomes pretty easy to move back and forth between two or three games at the same time, once you get the hang of it. Think of it as being like a story with multiple unrelated plotlines the author is switching your attention between. Start with two-player Throwdowns with two concurrent games, and work your way up to more of each.

The most satisfying form of Pyramid Throwdown sets two players against each other in a three-game match with all three games being played simultaneously.

Check out this sample game of Andy & Kristin playing a sample 3-game Pyramid Throwdown to see how it all works.

Scoring with Pyramids

One of the most simple and wonderful ways to play with the pyramids is to use them as score-keeping tokens. This is built into the design of a couple of pyramid games, such as Pyramid-Sham-Bo and Color Wheel. But pyramids make a fantastic alternative to paper & pencil when keeping score in any game with points.

One of the most simple and wonderful ways to play with the pyramids is to use them as score-keeping tokens. This is built into the design of a couple of pyramid games, such as Pyramid-Sham-Bo and Color Wheel. But pyramids make a fantastic alternative to paper & pencil when keeping score in any game with points.

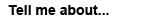

When using pyramids for keeping score, we give them values of 1 for Smalls, 5 for Mediums, and 25 for Larges. Think of them as being like Pennies, Nickels, and Quarters.

Pyramids make wonderfully exotic poker chips. When using pyramids instead of chips, we call it Martian Hold’em (since everyone’s favorite version of poker now is Hold’em.) Pyramids are actually better than poker chips in some ways, since larger-valued pieces feel more valuable when they’re actually bigger. (On the other hand, as the stakes go up you’ll be wishing for bigger pyramids…)

For a score-based game such as Hearts, in which you seek to avoid taking points, give everyone pyramids with a total value of the end-game amount. Then, as players gain points, they lose pyramids from their stash until they run out. For example, for a 100-point game, each player would start with 3 Larges, 4 Mediums, and 5 Smalls.

See also Andy's artciles about playing Hearts with pyramids and also using them for another classic favorite, Cosmic Wimpout.

Game Zero

This was mentioned above in the section about Younger Players, but it deserves its own shout-out. Game Zero is what we call the simple act of aimlessly playing with the pyramids.

Playing It Cool

Being a “cool” player was encouraged from the beginning, with the very first game including rules of comportment. Basically, this just our way of suggesting that being a good sport would make others more inclined to play games with you. More to the point, the rules of Icehouse are easily taken advantage of by those with the wrong attitude, i.e. “uncool” players, so it was particularly important to be "cool" in the original game.

See the Etiquette Notes at the end of the rules to Icehouse for more on these subjects.

Back in the days of Icehouse Tournaments at the Big Experiment, there was a special award for the player who best demonstrated the art of playing it cool. The player who was deemed “Cooler Than Ice” was chosen via secret ballot from among the competitors. Here’s what the award medallion looked like in 2003, with art by Petra Mayer: